By Mary Ann Christie Burnside

Although kindness can be misunderstood as an ineffectual or even superficial nicety, it’s neither. Like many amazing practices I’ve learned through mindfulness training, kindness is inspiring, powerful, courageous and wise. It’s also disarming, compelling and transformative. In any given moment, the kindness you offer to yourself or to others affects what happens in the very next moment.

Like mindfulness itself, kindness is a natural human quality that requires intentional action to realize it’s potential. And like mindfulness, research shows that kindness is good for our physical and our emotional well-being.

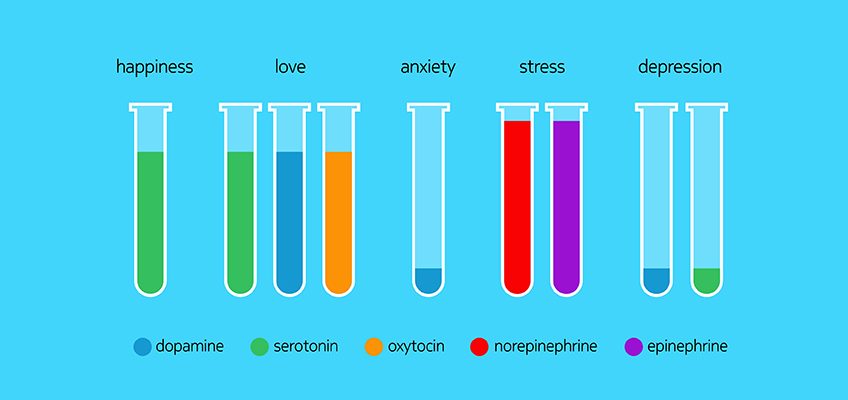

Studies show that thinking about, observing or practicing a kind act stimulates that vagus nerve, which literally warms up the heart and may be closely connected to the brain’s receptor networks for oxytocin, the soothing hormone involved in maternal bonding. Kindness also triggers the reward system in our brain’s emotion regulation center releasing dopamine, the hormone that’s associated with positive emotions and the sensation of a natural high.

Kindness—which reduces stress, anxiety and depression—can literally put us, and others, at ease. It works wonders in the relationships we have with ourselves and with everyone else, even with people we don’t know.

Try it next time you are out and about. Offer a kind word or gesture to someone you meet, or to someone who works in town or serves our community. Notice what happens. From a learning perspective, you’ll see that the effects are cumulative.

The more we practice, the better we get at it. This seems to be especially true in our most difficult moments. All of sudden, something shifts and we’ve chosen kindness instead of our habitual reaction. Consider this illustrative story of an American soldier, as told by Jack Kornfield, a wonderful teacher I had the privilege of learning from a couple of summers ago.

An American solider who’d been in Iraq was taking a mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) course offered by the Army upon his return. He had been struggling with anger and was severely critical of others. After a few weeks in the course, he began to learn the classical trainings in “lovingkindness” meditation, in which you repetitively practice sending goodwill to self and others.

One day he was waiting to pay for a few things on the express line at a local market. The woman in front of him not only had more than 12 items in her cart, she was also showing off a little baby to the cashier who was then gushing over and holding the baby. The cashier was taking quite a bit of time to talk with the woman in front of him. “Oh great!” he thought. “Not only is this woman in the WRONG line. She’s chit-chatting about her baby. This is taking much longer than I thought it would. I hate waiting. And I hate it when people don’t follow the rules. And why is this cashier so slow? I have half a mind to tell them both off right now!”

When he got to the register a few minutes later, he realized that the little baby really had been really cute and decided to mention this to the cashier. She replied “Oh, you think so? Thank you. That’s my son. Because my husband was recently killed in action, my mom takes care of my baby much of the time. She brings him here to work every day so I can see him.”

This exchange illustrates that no matter what our stories or histories, we can learn to be mindfully aware and train our minds to incline toward kindness. We get to choose how we want to be in the world.

More and more, the scientific community demonstrates that our brains can learn new things for most, if not all, of our lives. And human development and psychology teaches us that relational skills, unlike language and motor ones, do not automatically present themselves as we mature in age. The skills it takes to be in healthy relationship to self, other and our environment are ones we need to learn, once we decide to learn them.

The good news is that we can learn to be kinder. We literally train our brains every day by the things we repeatedly say and do. So when we practice kindness, we’re training our brains to get better at kindness. When we practice being frustrated, angry or otherwise stuck in our reactions, we get better at that. What we practice and how is our choice. Here are a few ideas on how to start practicing kindness:

1. Practice being kind to yourself. This is very important because we’re often less kind to ourselves than we are to others—even strangers! Think about what kindness to yourself would look like, then try it. Need ideas?

- Notice your self-talk (how you talk to yourself about yourself). If it seems negative, ask yourself if you would say this to a good friend and notice what happens.

- Practice treating yourself as well as you treat your friends, co-workers or family members.

- Sometimes, when we’re off or having a bad day, we start judging ourselves. Practice letting your experiences, thoughts and feelings in, whatever they are.

- Take a break when you need one.

- Engage in basic self-care. Get enough rest, eat when you’re hungry (and stop when you’re not) and exercise when you can (be sure to pick something you like to do).

2. It’s easy to be kind when were in a good mood. When we’re struggling, not so much. So next time you feel frustrated, angry or hurt, refrain from speaking or acting immediately. Take a moment. I help myself to remember this practice by using an acronym a teacher once gave me: S-T-O-P: S for stop, T for take a breath, O for observe what’s happening in and around you and P for practice responding rather than reacting.

3. Incline your mind toward kindness (and the positive emotions associated with kind action) by practicing “lovingkindness” meditation (see resources below). If you are skeptical about meditation, you can think of these exercises as practicing affirmations to bring kindness into your daily life as a way to increase well-being to the benefit of yourself and others.

Source: Mindful http://www.mindful.org/intentional-acts-of-kindness/